Confident your EF Core models are “fine” because the app runs? That’s exactly how silent mapping bugs slip into production and cost you hours of head‑scratching migrations. In this post I’ll show you what to configure with Data Annotations, what to push to Fluent API, and how to make both play nicely – with clear patterns you can drop into your project today.

Why this matters (and what you’ll get)

If you’ve ever deployed and later discovered: strings saved as NVARCHAR(MAX), decimals rounded in reports, cascade deletes nuking half the database – this post is for you. We’ll cover:

- The mental model: Conventions → Data Annotations → Fluent API (precedence)

- Property rules (nullability, length, precision, Unicode)

- Keys, indexes, alternate keys, composites

- Relationships (1-1, 1-many, many‑many), delete behaviors

- Owned types, value objects & value converters

- Inheritance mapping (TPH/TPT/TPC – when and how)

- Global query filters, shadow properties, check constraints

- Scalable configuration patterns (IEntityTypeConfiguration, assembly scanning)

- Common pitfalls & a practical checklist

Throughout I’ll share the shortcuts I use after 15 years in .NET projects.

The mental model: who wins?

EF Core builds the model in layers:

- Conventions – sensible defaults inferred from CLR types and names.

- Data Annotations – attribute hints on the entity class.

- Fluent API – explicit rules in

OnModelCreatingor configuration classes.

Rule of thumb: when both specify the same thing, Fluent API wins. I treat annotations as local, obvious constraints; Fluent as the centralized, unambiguous source of truth.

Analogy: Annotations are sticky notes on the book page, Fluent is the table of contents the whole team reads.

Quick baseline: a tiny domain

We’ll use a small HR domain:

public class Employee

{

public Guid Id { get; set; }

// Local, obvious constraints are perfect for annotations

[Required]

[MaxLength(120)]

public string FullName { get; set; } = default!; // non-null reference type

[MaxLength(254)]

public string? Email { get; set; }

public decimal MonthlySalary { get; set; }

// Relationship to Department (by convention recognized by *Id)

public int DepartmentId { get; set; }

public Department Department { get; set; } = default!;

// Owned value object

public Address Address { get; set; } = new();

// Soft delete flag

public bool IsDeleted { get; set; }

}

public class Department

{

public int Id { get; set; }

[Required, MaxLength(80)]

public string Name { get; set; } = default!;

public ICollection<Employee> Employees { get; set; } = new List<Employee>();

}

// Value object

public class Address

{

public string Street { get; set; } = string.Empty;

public string City { get; set; } = string.Empty;

public string Zip { get; set; } = string.Empty;

}

Now let’s wire it up with a clean Fluent configuration that scales.

Scalable configuration with IEntityTypeConfiguration

I avoid monster OnModelCreating. Instead, I split per entity and register all at once.

public class AppDbContext : DbContext

{

public DbSet<Employee> Employees => Set<Employee>();

public DbSet<Department> Departments => Set<Department>();

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder)

{

// Pick up all IEntityTypeConfiguration<T> from this assembly

modelBuilder.ApplyConfigurationsFromAssembly(typeof(AppDbContext).Assembly);

// Global rules can stay here (e.g., query filters)

modelBuilder.Entity<Employee>()

.HasQueryFilter(e => !e.IsDeleted);

}

}

Employee configuration

public sealed class EmployeeConfiguration : IEntityTypeConfiguration<Employee>

{

public void Configure(EntityTypeBuilder<Employee> b)

{

b.ToTable("Employees");

// Key + alternate key example

b.HasKey(e => e.Id);

b.HasAlternateKey(e => e.Email) // nulls ignored at runtime; index still useful

.HasName("AK_Employees_Email");

// Property rules

b.Property(e => e.FullName)

.IsRequired()

.HasMaxLength(120)

.IsUnicode();

b.Property(e => e.Email)

.HasMaxLength(254)

.IsUnicode(false); // store as varchar

// Money/decimal precision – avoid rounding surprises

b.Property(e => e.MonthlySalary)

.HasPrecision(18, 2);

// Indexes

b.HasIndex(e => e.Email)

.IsUnique()

.HasDatabaseName("UX_Employees_Email");

b.HasIndex(e => new { e.DepartmentId, e.FullName })

.HasDatabaseName("IX_Employees_Department_FullName");

// Relationship

b.HasOne(e => e.Department)

.WithMany(d => d.Employees)

.HasForeignKey(e => e.DepartmentId)

.OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.Restrict);

// Owned type mapping

b.OwnsOne(e => e.Address, oa =>

{

oa.Property(a => a.Street).HasMaxLength(160);

oa.Property(a => a.City) .HasMaxLength(80);

oa.Property(a => a.Zip) .HasMaxLength(20).IsUnicode(false);

oa.ToTable("Employees"); // table-splitting (stay in same table)

});

// Shadow property for auditing

b.Property<DateTime>("LastModifiedUtc")

.HasDefaultValueSql("GETUTCDATE()")

.IsRequired();

// Check constraint

b.ToTable(tb => tb.HasCheckConstraint("CK_Employees_Salary_Positive", "MonthlySalary >= 0"));

}

}

Department configuration

public sealed class DepartmentConfiguration : IEntityTypeConfiguration<Department>

{

public void Configure(EntityTypeBuilder<Department> b)

{

b.ToTable("Departments");

b.HasKey(d => d.Id);

b.Property(d => d.Name)

.IsRequired()

.HasMaxLength(80)

.IsUnicode();

b.HasIndex(d => d.Name).IsUnique();

}

}

Tip: Team rule I use – properties get annotations, everything cross‑cutting goes Fluent (indexes, keys, relationships, check constraints, converters, table names, filters).

Relationships done right (and safe deletes)

One‑to‑many (we used above)

- FK property

DepartmentId+ navigationDepartmentis enough for conventions. - Control deletes: prefer

DeleteBehavior.Restrictin OLTP apps to avoid accidental cascades.

One‑to‑one

public class User

{

public int Id { get; set; }

public UserProfile Profile { get; set; } = default!; // required 1:1

}

public class UserProfile

{

public int Id { get; set; } // shares PK with User

public string Bio { get; set; } = string.Empty;

}

public sealed class UserConfiguration : IEntityTypeConfiguration<User>

{

public void Configure(EntityTypeBuilder<User> b)

{

b.HasOne(u => u.Profile)

.WithOne()

.HasForeignKey<UserProfile>(p => p.Id)

.OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.Cascade);

}

}

Many‑to‑many (skip entity vs explicit join)

For simple “tagging” scenarios, use skip navigations:

public class Course { public int Id { get; set; } public string Name { get; set; } = ""; public ICollection<Student> Students { get; set; } = new List<Student>(); }

public class Student { public int Id { get; set; } public string FullName { get; set; } = ""; public ICollection<Course> Courses { get; set; } = new List<Course>(); }

public sealed class CourseConfiguration : IEntityTypeConfiguration<Course>

{

public void Configure(EntityTypeBuilder<Course> b)

{

b.HasMany(c => c.Students)

.WithMany(s => s.Courses)

.UsingEntity(j => j.ToTable("StudentCourses"));

}

}

When you need payload (e.g., grade, enrolled date), model an explicit join entity.

Owned types & value objects

Value objects are perfect as owned types. We mapped Address into the same table (table‑splitting). If you want a separate table per address, map with OwnsOne + ToTable("Addresses") and add a FK.

For more complex value objects (e.g., Money with decimal Amount + string Currency), use a Value Converter:

public readonly record struct Money(decimal Amount, string Currency)

{

public override string ToString() => string.Create(System.Globalization.CultureInfo.InvariantCulture, $"{Amount:0.00} {Currency}");

}

public sealed class MoneyConverter : ValueConverter<Money, string>

{

public MoneyConverter() : base(

v => $"{v.Amount}|{v.Currency}", // to provider

v => {

var parts = v.Split('|');

return new Money(decimal.Parse(parts[0]), parts[1]);

}) {}

}

public sealed class MoneyComparer : ValueComparer<Money>

{

public MoneyComparer() : base(

(a,b) => a.Amount == b.Amount && a.Currency == b.Currency,

v => HashCode.Combine(v.Amount, v.Currency),

v => new Money(v.Amount, v.Currency)) {}

}

// Usage in configuration

b.Property<Employee>("Bonus")

.HasConversion(new MoneyConverter())

.Metadata.SetValueComparer(new MoneyComparer());

Why a comparer? Without it EF may not detect changes for value objects correctly.

Precision, Unicode, and other column details

- Strings: default is Unicode (

NVARCHAR). For emails/identifiers, save space with.IsUnicode(false). - Decimals: always set

.HasPrecision(total, scale)to avoid provider defaults (e.g., money rounding). - DateTimes: prefer UTC in the database; use

GETUTCDATE()defaults and handleDateTimeKindin application code. - Computed columns:

.HasComputedColumnSql("[Price] * [Qty]", stored: true)for materialized computed values.

Indexes, alternate keys, composites

b.HasIndex(e => e.Email).IsUnique();

b.HasIndex(e => new { e.DepartmentId, e.FullName })

.HasDatabaseName("IX_Employees_Department_FullName");

b.HasAlternateKey(e => e.Email); // logical identity besides PK

// Composite key example (prefer Fluent)

b.HasKey(x => new { x.PartAId, x.PartBId });

When to use an alternate key? When you need identity semantics beyond the surrogate PK – like natural keys (Code, ISO code, etc.) while still keeping a GUID/int PK for joins.

Inheritance mapping – pick intentionally

- TPH (Table‑Per‑Hierarchy): single table + discriminator (fast, simplest, can be sparse). Default.

- TPT (Table‑Per‑Type): normalized across tables (clean schema, joins per query).

- TPC (Table‑Per‑Concrete): separate tables per concrete type (no joins, but duplication).

Example TPH:

public abstract class Document { public int Id { get; set; } public string Title { get; set; } = ""; }

public class Invoice : Document { public decimal Total { get; set; } }

public class Contract : Document { public DateTime ValidUntil { get; set; } }

public sealed class DocumentConfiguration : IEntityTypeConfiguration<Document>

{

public void Configure(EntityTypeBuilder<Document> b)

{

b.ToTable("Documents");

b.HasDiscriminator<string>("DocType")

.HasValue<Invoice>("Invoice")

.HasValue<Contract>("Contract");

b.Property("DocType").HasMaxLength(32).IsUnicode(false);

}

}

Switching strategies later is a migration-heavy change – choose early.

Global query filters & soft delete

We added HasQueryFilter(e => !e.IsDeleted). Remember:

- Filters apply to all LINQ queries unless you call

.IgnoreQueryFilters(). - Use with care on multi-tenant systems (include tenant predicate). Example:

modelBuilder.Entity<Order>()

.HasQueryFilter(o => !o.IsDeleted && EF.Property<Guid>(o, "TenantId") == _tenantContext.TenantId);

Concurrency, timestamps, and optimistic locking

Two practical patterns:

- Mark a property as a concurrency token:

b.Property(e => e.Email)

.IsConcurrencyToken();

- Use a binary rowversion column:

public byte[] RowVersion { get; set; } = Array.Empty<byte>();

b.Property(e => e.RowVersion)

.IsRowVersion() // or: .IsConcurrencyToken().ValueGeneratedOnAddOrUpdate()

.IsRequired();

Then handle DbUpdateConcurrencyException to resolve conflicts.

Seeding data that survives migrations

b.HasData(new Department { Id = 1, Name = "HR" },

new Department { Id = 2, Name = "Engineering" });

For many rows, prefer an external seed mechanism (scripts or DbContext initializer) to keep migrations clean.

Ignoring, backing fields, and shadow properties

- Ignore a CLR property:

b.Ignore(x => x.SomeNotMappedProperty); - Backing fields (encapsulation):

private readonly List<string> _tags = new();

public IReadOnlyCollection<string> Tags => _tags;

b.Metadata.FindNavigation(nameof(Post.Tags))!

.SetPropertyAccessMode(PropertyAccessMode.Field);

- Shadow properties (no CLR):

b.Property<DateTime>("CreatedUtc").HasDefaultValueSql("GETUTCDATE()").

Putting it together: a migration‑friendly checklist

Before you run Add-Migration:

- All relationships have explicit delete behaviors (

Restrict/NoAction/Cascadeas intended) - Decimals and DateTimes configured (precision, defaults)

- Indexes and uniqueness captured in Fluent

- Owned types mapped intentionally (same table vs separate)

- Query filters include tenant/soft‑delete conditions

- Alternate keys only when necessary (natural identity)

- Value converters & comparers for value objects

- Check constraints for domain invariants in the DB

- Configuration classes in place and discovered via

ApplyConfigurationsFromAssembly

Paste this into your PR template – I do.

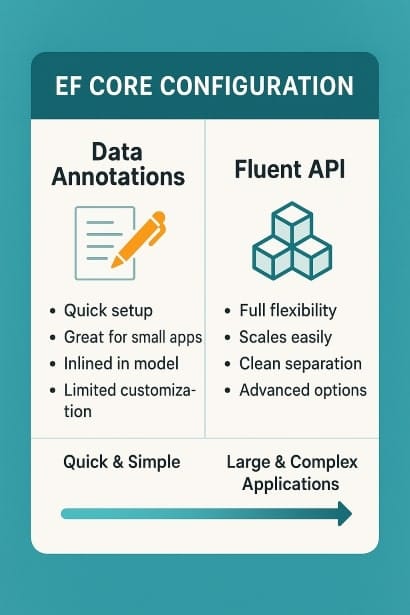

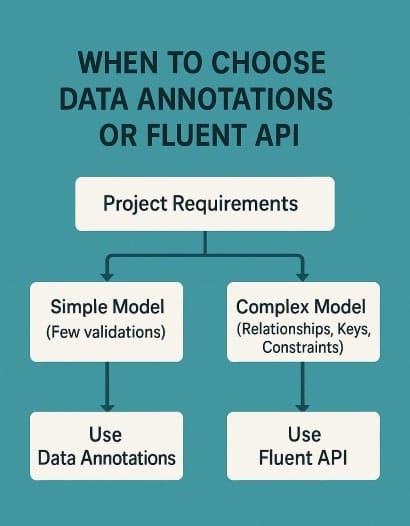

When to choose Annotations vs Fluent (pragmatic rules)

Use Data Annotations when:

- The rule is obvious and strictly local to a property (

[Required],[MaxLength],[Unicode(false)]). - You want quick readability inside the entity class.

Use Fluent API when:

- Defining relationships, keys, indexes, converters, filters, constraints, table names/schemas.

- You need cross‑cutting consistency across many entities.

- You don’t want to couple domain model to EF attributes (clean domain).

Avoid duplication: don’t put [Required] and .IsRequired() on the same property unless you’re deliberately overriding – future you will thank you.

Common pitfalls I keep seeing (and how to avoid them)

- Nullable reference types != required in DB. If

string?is nullable in C#, the column will be nullable unless you mark it required via annotation/Fluent. decimalwithout precision becomes provider default – always setHasPrecision.- Silent cascades. Conventions might set cascade; set delete behaviors explicitly.

- Big strings everywhere. Default

NVARCHAR(MAX)can hurt indexes; set lengths. - Value objects without comparers. EF won’t detect modifications – add a

ValueComparer. - Global filters that break admin tools. Remember

.IgnoreQueryFilters()where appropriate. - Monster

OnModelCreating. Split intoIEntityTypeConfiguration<T>classes.

FAQ: Data Annotations & Fluent API in practice

Fluent API overrides annotations. Keep duplicates to a minimum; prefer a single source of truth.

They couple the model to EF. If you want pure domain classes, prefer Fluent. Pragmatically, I still allow harmless, readable annotations like [Required]/[MaxLength].

b.HasKey(x => new { x.PartAId, x.PartBId }); – Fluent only.

b.Property(x => x.Total).HasComputedColumnSql("[Qty]*[Price]", stored: true);

Prefer Fluent: b.HasIndex(x => x.Email).IsUnique(); It’s explicit and discoverable.

If it has no identity and only lives with the owner, it’s a value object → owned type. If it has lifecycle/queries of its own, make it an entity.

Small, stable sets with HasData. For large or changing data, use scripts or app‑level seeding to avoid noisy migrations.

Conclusion: Configure once, ship with confidence

Getting EF Core configuration right is less about memorizing every API and more about choosing the right place for each rule. Put local constraints in annotations, move cross‑cutting and relational rules to Fluent, and organize everything with IEntityTypeConfiguration. Do this, and your migrations become predictable, your queries stable, and your future self – grateful.

What’s your personal split between annotations and Fluent (50/50? 20/80?) and why? Drop a comment – I’m curious how teams balance readability vs purity.